I’ve always been a bit skeptical when someone says, “Let’s start with the fundamentals.” What even are fundamentals, and why should we start with these? Why must I take prerequisite courses before I immerse myself in the stuff I really want to study or relevant this moment?

A professor I have a lot of respect for once brought up this question, which is one of the best questions I’ve ever heard and can bring out the most interesting ideas from anyone, went something like this:

“What important truth do very few people agree with you on?”

This essay is an attempt at finding the answer I would give, an exploration of my own animosity towards ordered learning by trying to put forward an argument against the concept of prerequisites (both inside and outside of school), so I can see if my feeling stands to reason.

I can’t be sure this actually happened, but I would believe it. From the fresh perspective of any toddler, how is the concept of quarks more unreachable than dinosaurs, or fairies?

At some early point in our lives we had no prior contact with any of the dinosaurs, fairies, or quarks. And it’s hard to argue that one is objectively more complex than the other. Sure, maybe we have enjoyed the experience of birds or lizards (what if: they were bigger and more scary??), and really capable people (what if: they could fly??). These prior experiences make connecting to farther concepts more manageable, making them supposedly simpler. But experiences are everywhere, some just rarer than others. Have you ever squinted at little bits of dust, and watch them suddenly stick together like magnets? (what if: they were much smaller??) Have you ever tried to blink really fast? (what if: you tried blinking so fast that sometimes no light comes in at all?)

I think the point I’m trying to make is that complexity of topics is only convention.

They say that if you cannot explain something in simple terms, you do not really understand it. This implies that everything that can be learned can be distilled into ideas simpler than it. One possibility is that there are loops, like in the game of rock paper scissors. Complexity is not a ranking, but a system of directional pointers. Another possibility is that there are infinitely many terms, each simpler than the last. However, if there are infinitely many, how can we hope to explain them all? Do we understand anything at all?

It’s common to think of learning as building a tower: you start with the foundation on the ground, and layer by layer one adds structural support for the next. With no foundation, new concepts fall down and are forgotten. However, I want to challenge that model. I think the gravity on this planet of learning pulls each of us in different directions, depending on our experiences and aspirations. How can we all build the same tower when “up” is defined differently? Also, we may already have similar structures nearby, and all that’s needed is to build a bridge. To me, the ground-up tower model limits our thought because it emphasizes only one line of reasoning.

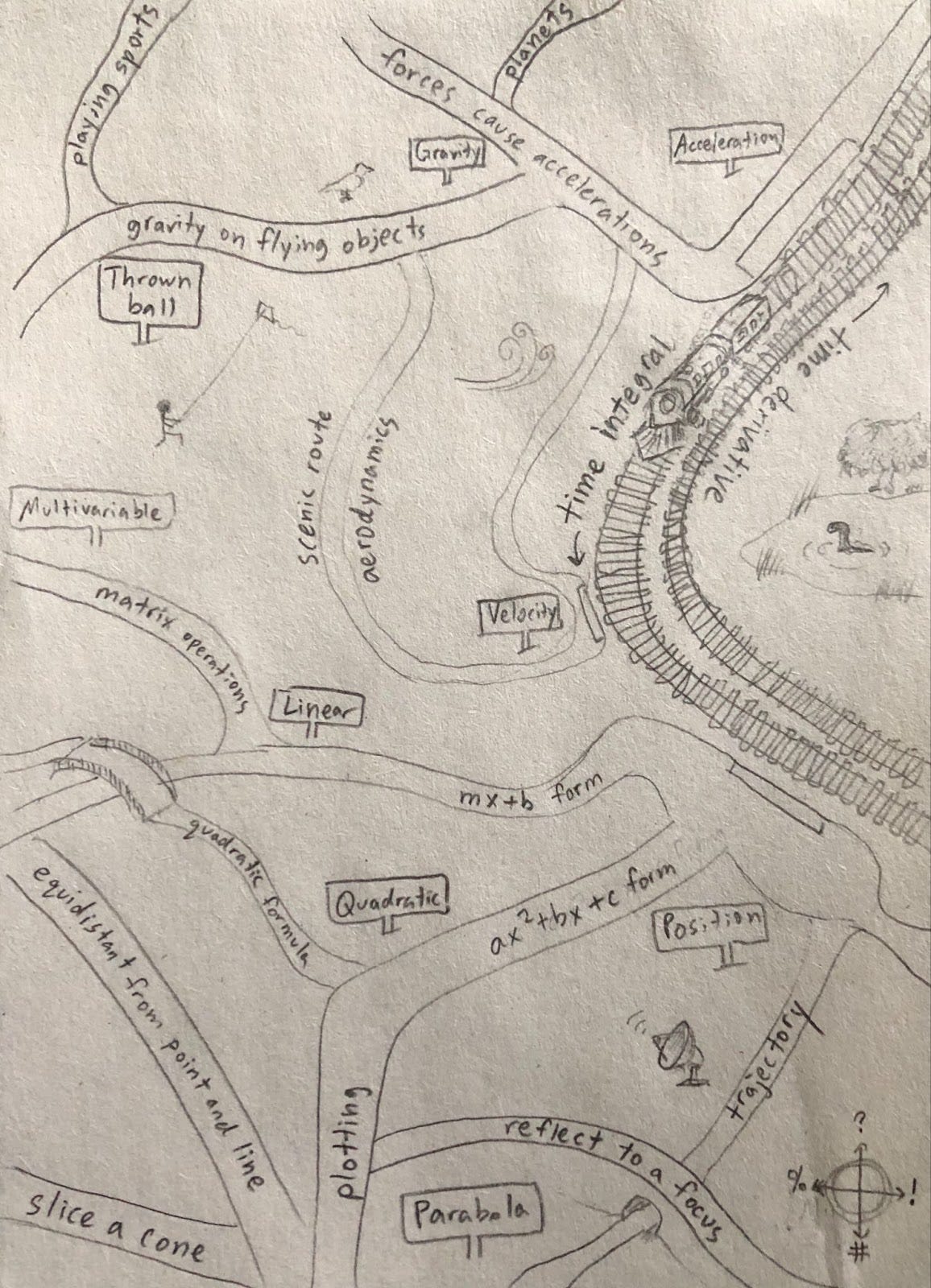

I believe that when we think, we are traveling. Thoughts are the roads we walk down, and topics the regions we visit on our way. Just like how cities are regions where many roads converge and roads connect city to city, topics are where thoughts meet each other and thoughts are how we get from topic to topic. Common beliefs become daily commutes, while forgotten experiences become overgrown trails. When we reason, we take turns onto various routes of thought until we’ve made our way from assumptionland to conclusionland.

In this model, learning is exploring new roads, getting to new cities, and building your imaginary atlas. Sometimes this comes in the form of wandering by yourself, either with or without an aim. Other times you may get navigation directions from someone:

"After you throw a ball, there is only the force of gravity acting on it. This causes the ball to have a constant acceleration downwards. Integrate acceleration with time to get a vertical velocity that decreases linearly, and then integrate again to get a position that decreases quadratically. This makes the ball travel in the shape of a parabola.”

Models are never perfect, but I like that the imaginary atlas captures that there is often more than one path to a topic, and paths go both ways. To get to parabolas, you don’t have to start with throwing balls—you could be designing a radar dish, or slicing a cone. Conversely, you don’t have to learn about parabolas and their ability to focus waves before you start to think about throwing balls.

The tower model suggests that some topics are more fundamental than others, and it would be crazy to move on without building a solid foundation. However, if topics are cities and the thoughts the roads that consist them, I don’t believe that we must thoroughly explore a city before moving onto the next one. Maybe the next city is only accessible through this one. For example, I’m not sure if there’s a way to learn to use the quadratic formula without knowing anything about multiplication. You would have to travel through multiplication first, but only the parts which matter in this context. Just move on with what you need.

Have you ever bought something just because it’s on sale? A winter coat, 40% off. The newest electric hand drill, buy one now and you get a set of bits for free, plus the battery charger, for a limited time! It’s summer and you can’t think of anything that needs holes put into it, though these bargains might come in handy one day. Better collect them now that it’s convenient, you think. You can’t collect everything, of course, because your home is only so big, and there are too many exciting things in the world. The amount you “should” get, in a sense the “optimal” decision in this case, would depend on how accurate you are when predicting that something would be useful in the future, and how easily you are able to get it later on.

So I admit there are some useful purposes of learning “foundations”, especially in school:

to trust society’s predictions on what’s needed in the future and then preemptively exploring the options

to learn something in an environment that happens to make it easy because a lot of people are traveling the same path at the same time

course curriculum ~ product sale

to establish a stable channel for communication

yeah, just go down <well-known street>, turn left, and you’ll find it

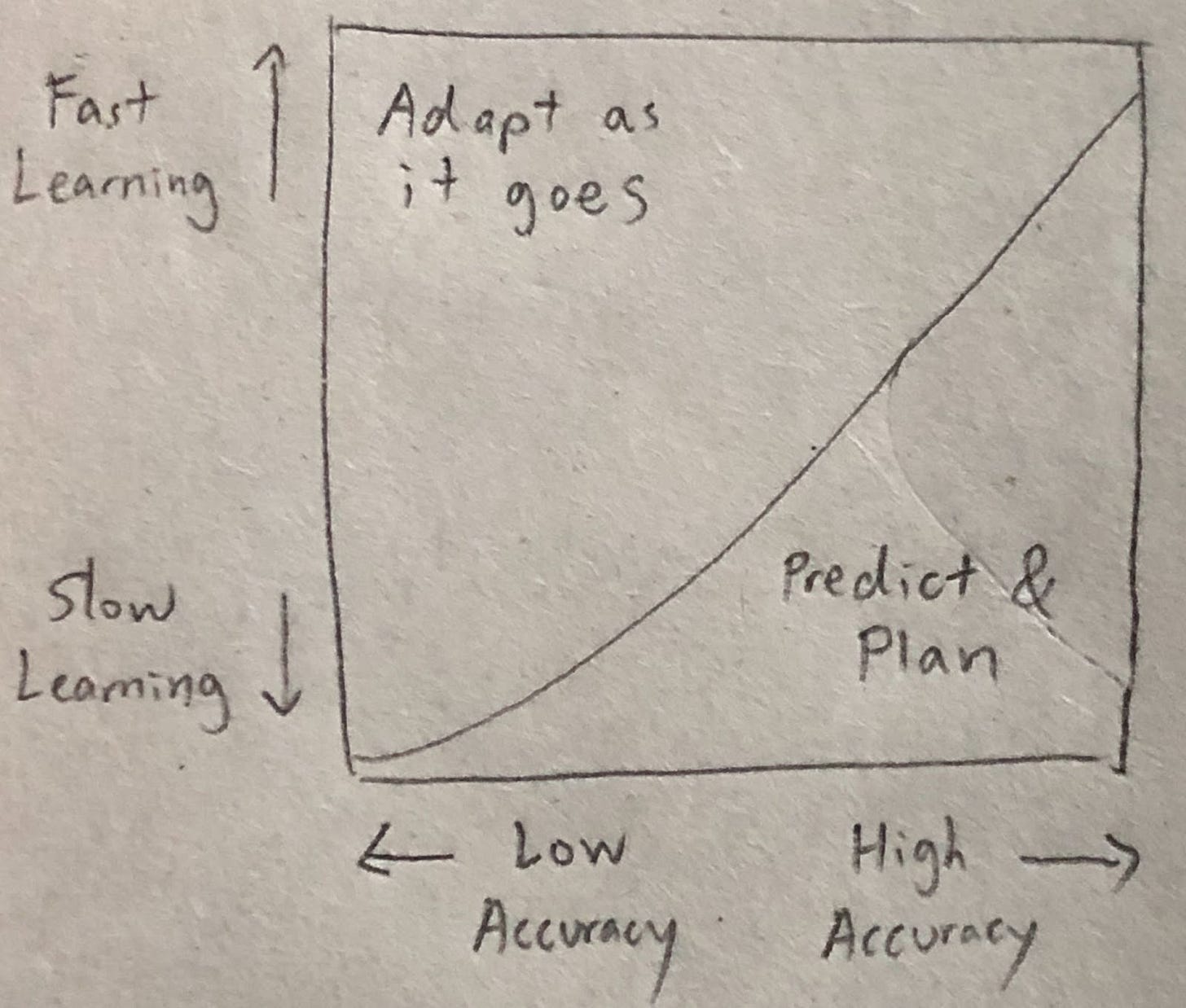

If the people before us are able to accurately predict what knowledge would serve as the best tools to solve tomorrow’s problems, it would be a good idea to learn them before the problems become immediate. There is a tradeoff here with the accuracy rate of the predictions and the speed we can learn new tools. If the accuracy is too low or we can quickly learn new tools as the problems appear, it would be more effective to simply react to the current situation and learn what is necessary.

In control systems, there are generally two components to choose what effort to apply: feedforward and feedback. Feedforward is looking at where the target is and trying to calculate a control effort to get there. This relies on having a good model to predict what happens if some amount of effort is applied. Feedback is reacting to errors in real-time, applying a control effort in the direction that will minimize the error. Both are important and can exist simultaneously, but feedforward is generally more useful when the system is predictable, or moving slow. Feedback allows for more dynamic movements and adaptations in a fast changing and chaotic environment.

I believe that there is a trend of our environment moving to the upper left of the plot, with the world moving faster making it harder to make accurate predictions, and new tools making it possible to gather information about something in a few minutes that might have taken previous generations days.

If we are accelerating, the value of feedforward (optimizing decisions based on forecasts of the world) is declining because it’s harder to accurately predict what’s going to happen. The value of pre-building a human database, of collecting tools on sale in hopes of them being useful later, is declining because it’s getting easier to store and retrieve information outside the brain.

What we call foundations are the pathways that people most commonly take, the famous ones, those lines of reasoning that most people in the field will understand, making them common grounds for sharing information and debate. This, I feel, will remain regardless of acceleration and the chaos of the world. However, for foundations to serve the purpose of a common language, there really is no need to understand it in its entirety before starting to use it. How do you even fully understand a language? It varies between people, and it changes all the time. Learn enough, and know that most language learning comes from immersion.

Of course, I’m not sure if my beliefs about “foundations” will stay the same. That would again be like making all decisions based on a fixed model of the world. With a tight feedback loop with the environment, the model will evolve accordingly. It’s just that at the current moment, I think prerequisites are probably overrated.

“Centuries of centuries and only in the present do things happen” - Jorge Luis Borges, The Garden of Forking Paths

Absolutely beautiful. One of the best things I've read this year.

I find myself agreeing with you. The way I think about knowledge is by fractals. Each subject is a fractal set and embedded within it is an infinite amount of complexity, depending on the frame of reference. Human learning seems to be via surface area traversel + leaping between subjects at the time when it's convenient.

So really, when you learn a subject with a goal in mind, so long as you learn enough about that specific aspect of the subject, you can use it to forward your journey. Even subjects thought of to be extremely complex are very easily reducible. Once reduced, you can fill in gaps and increase resolution of knowledge as you gain more knowledge. Examples include propulsion, orbital mechanics, control theory, cs etc. There's a point of good enough. I think the best learning I've done is that with a goal in mind.

For example. I need to learn enough RobotC to make this robot move in circles. Great, there's a quantifiable goal here, and so long as you reach that point, you are chilling, you have a good stopping point for the subject and you will spend only as much time as is productive for you to spend.

That is not to denigrate learning via curiosity. Both are extremely valuable, but play a different role and I choose to not focus on curiosity based learning here.